Paul Cezanne and Amadeo Modigliani

Paul

Cezanne: Painting People at the National Portrait Gallery and Amadeo Modigliani

at the Tate Modern on the 26th & 27th of November

2017

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906) was

born in Aix-en-Provence in the south of France but soon moved to Paris to be

with his childhood friend, the writer Emile Zola. Throughout his life he divided his time

between Paris and Aix. Cezanne’s father,

Louis-Auguste Cezanne (1798-1886) had accrued a fortune firstly by selling hats

and then as a banker. He wanted his son to be a lawyer. However, Cezanne’s

ambition was to be an artist. His wish to

be purposefully engaged in a creative life and to marry the woman he loved were

all opposed by his father who also happens to be the subject of the first major

painting in this exhibition. Cezanne’s

painting of his father, ‘The Artist’s Father reading L’Evenement’ (oil on canvas, 1866) demonstrates the dominant

influence of Cezanne’s early life.

Louis-Auguste is sitting in a chair reading a newspaper, his figure is

firmly contextualised with concrete details of his study and local environment,

a sturdy functionary ensconced in his armchair.

The paper published Emile Zola’s defence of the artists rejected by the

Paris Salon in 1866 which included Cezanne.

Therefore, Cezanne is alluding to

a recent, topical event that was of urgent relevance. The portrait was completed with a palette

knife, this technique evokes a rough, sculptural style at odds with the

refinement of Cezanne’s later works.

Cezanne described this early style as his maniere couillarde (from coquilles,

testacles) meaning a crude, ballsy style, visceral and muscular rather than

sensitive and delicate.

Other works from this

early period include ten portraits of Uncle Dominique (1817 -?) who worked as a

bailiff. They were also completed with

palette knife, dark hues and tones dominate. Painted over ten days in 1866-7, roughly a

portrait a day, Uncle Dominique wears differing costumes, a turban, smock and

blue cap. Cezanne tellingly depicts

Uncle Dominique as a lawyer, the profession he rejected, in a reference to

Provencal art that liked to satirise members of the legal or ecclesiastical

professions. Clearly Uncle Dominique was

in on the joke, the comedian Cezanne would rise to be a much more than a local

functionary. Uncle Dominique was

obviously prepared to wear fancy dress to underline a blatant nudge to

Cezanne’s father who was probably looking the other way.

Louis-Auguste disapproved

of Cezanne’s relationship with Hortense Fiquet (1850-1922) who later became

Madame Cezanne. Initially their

relationship was furtive, concealed from his father until their marriage in

1886 when Cezanne’s father died. They

had met in 1869 and their son, also called Paul, was born in 1872. Cezanne’s most significant portrait of

Hortense was Madame Cezanne in a Red

Armchair (oil on canvas, 1877) of which the German poet Rainer-Maria Rilke

said: “the consciousness of her presence has grown into an exultation which I

perceive even in my sleep: my blood describes her to me.” Cezanne’s relationship to Hortense which was

furtive then undisguised but ended prematurely when the couple drifted apart

towards the end of Cezanne’s life, is documented in many paintings. This is the most significant of these

portraits of Hortense, also clearly a monumental artwork that encapsulates

Post-Impressionism and tends towards 20th century art movements such

as Cubism and Abstraction. Hortense is

individualised on her throne, her dress shimmers with myriad colours and her

face is blank and expressionless.

Essentially, this is an anti-portrait, unflattering, unsensational,

Madame Cezanne’s misery lurks in every detail and brushstroke from the

perfected depiction of her chair, dress and hands clasped together. The tension created by the interlocking

elements creates an artwork that is an essential critique of portraiture and

the torpor of bourgeois ordinariness.

Each succeeding portrait of Madame Cezanne exudes misery, masterpieces

of lugubrious intent such as Madame

Cezanne in a Striped Dress (1885-6, oil on canvas), Madame Cezanne in a Red Dress (1888-1890, oil on canvas), Madame Cezanne in Blue (1886-7, oil on

canvas). These are mesmerising portraits

of sculptural even architectural design with intricate usage of space to

emphasize the artists theme of a family being gradually destroyed by an artists

obsession with the ineluctability of artistic form.

Cezanne was free to

pursue his vocation as artist by the bequest he received from his father, he could

paint as and when he liked and did not have to complete commissions. Consequently, he unfailingly attempts to

portray his sitters in an unflattering light, defying convention and the

dominant aesthetic of the time, Impressionism.

These sculptural paintings of his, completed with a palette knife, lead

on to an architectural conception of painting as he sought to replace the

immediacy of the Impressionists with an art that could contain the permanence

of the Old Masters. For this reason, he

is regarded as a bridge between Impressionism and the 20th century,

both Picasso and Matisse remarked that Cezanne is ‘the father of us all.’

Like Rembrandt, Cezanne

documented his life through a series of self-portraits in which elements of his

development as an artist can be perceived but also his own personal evolution

from revolutionary young artist to respected member of the bourgeoisie. Cezanne’s friendships with the novelist Emile

Zola (1840-1902), Paul Alexis (1847-1901) and other friends from Aix and Paris

summarise his early life of struggle and revolutionary ardour. (The exhibition tells us that it was once

thought that Zola’s novel L’Oeuvre or

The Masterpiece (1886) which depicts the struggles of an artist ended their

friendship because it is very clear that the artist is Cezanne but much later

correspondence between Cezanne and Zola has been discovered falsifying this

claim.) The exhibition presents two self-

portraits from 1875 when Cezanne was 36, Self-Portrait

and Self-Portrait, Rose Ground (oil

on canvas). The self-portrait was

developed from a mirror rather than a photograph because Cezanne used both

means. He is thickly bearded and bald

too, he gazes from the canvas with great intensity, looking the epitomy of a

wild Bohemian artist. The works were

painted when Cezanne was on the periphery of the Impressionists, he

demonstrated these works at the 1st and 3rd Impressionist

exhibitions away from the Paris salon.

Unflattering and unconventional, these works seem to allude to the

theories of Zola outlined in his Rougon-Macquart series of novels that debate

the influence of genes and hereditary.

The 20 novels of the series illustrate how the fates and destinies of

two families, the “good” Rougons and the “bad” Macquarts, are shaped by

heredity and environment. Creativity and

insanity, Zola implies, are closely connected since the protagonist of L’Oeuvre Claude Lantier, a Macquart,

displays the symptoms of mental illness in his obsession with painting that

also run in his family but as an uncontrolled obsessive-compulsive

disorder. Like Lantier, Cezanne was

rejected by the art establishment and in this portrait visionary and madman

seem to merge. Incidentally, Emile Zola

is depicted in Cezanne’s work Paul Alexis

Reading a Manuscript to Zola (1869-70, oil on canvas). This becomes more apparent when later

self-portraits of Cezanne are viewed such as Self-Portrait (1880-81) and Self-Portrait

in a White Bonnet (1881-82, both oil on canvas). In these Cezanne appears calmer, he exhibits

a neatly trimmed beard, his father now approved of his choice of

profession. The works demonstrate Cezanne’s

‘constructive brushstrokes’, patches of paint applied in a parallel, usually

diagonal direction. By the time of his

two works, Self-Portrait with Bowler Hat

(1885-6, both oil on canvas), Cezanne is no longer the wild eyed

revolutionary. He is now a bourgeois

complete with bowler hat, a symbol of affluence and success. He has inherited his father’s fortune, he is

married, and his young wife has a son.

Cezanne’s final self-portrait, Self-Portrait

with Beret (1898-1900, oil on canvas) illustrates the artist’s willingness

to document his own life yet the expression on Cezanne’s face, blank and

miserable, is essentially unchanged.

Towards the end of his

life Cezanne’s marriage finally ended and he now rarely saw his wife and

child. Instead Cezanne took to painting

the people of Aix. These paintings, such

as Old Woman with Rosary (1900, oil

on canvas) are suffused with tenderness and close observations of the lives of

the ordinary people Cezanne observed. (Although some saw a look of cynicism

about the old woman saying that she was a former nun who had lost her faith and

was then taken in. However, this story

was uncorroborated.) Cezanne completed

two portraits of his gardener, The

Gardener Vallier (1905-6) and works that take figures from his series of

card player portraits and provide a closer observation such as Man in Blue Smock (1897), Man with Pipe (1891-6) and even Woman with Cafetiere (1895) where forms

like the cone and cylinder are exemplified.

Cezanne kept painting right up to the very end and, by this time, his

work was beginning to be recognised in the art centres that had often rejected

him. Today he is a household name like

his friend Zola.

Amadeo Modigliani was a

Sephardic Jew born in Livorno, Italy in 1884 and who died in Paris in 1920 at

the young age of 35. He spuriously

claimed that the philosopher Spinoza was an antecedent and when he was 21

gravitated towards Paris where he became part of the cutting edge of

experimentalists and pioneers. However,

Modigliani was to suffer from the bitter, populist anti-semitism that was

common in France at that time. Consequently,

he was forced to endure poverty which afflicted him throughout his short

life. At first, he lived in Montmartre,

the fashionable art quarter of Paris of the 19th century, and later

moved to Montparnasse which became the place to be for the generation of les Annees Folles (the crazy years from

1918-1939). Modigliani had a wide circle

of friends and he painted them too but also intimate, personal paintings of his

wife and a series of nudes that scandalised Paris.

Initially he painted in

the Post-Impressionist manner established by Paul Cezanne who was his first,

important influence. In early works the

diagonal brushwork and architectural concept of space and the interrelationships

of figure and context intimate Cezanne yet Modigliani was also attempting to

develop his own signature which he eventually began to realise. Modigliani gradually began to simplify

facial features and colour into a format indicating primitive art or even the

pre-Raphaelite painting of the first Renaissance (that occurred with the work

of Giotto in the 13th century).

As well as painting Modigliani

had a parallel career as a sculptor. In Modigliani’s

sculptures his signature style, a set of clichés or shorthand, began to

evolve. He was heavily influenced by the

Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) who had also moved from his

native Romania to Paris. However,

Modigliani’s work was short-lived. By

1911 he had finished his work as a sculptor altogether. He liked to visit the non-Western art

collections in the Musee d’Ethnographie du Trocadero and Musee Guimet with

Brancusi and another friend, the Portugese painter Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso. He made studies of Caryatids, plinths, supports

and pillars in feminine forms used in ancient Greece and Rome. The émigré Russian poet, Anna Akhmatova

(1889-1966), with whom he had an affair, is drawn in a style reminiscent of the

Egyptian statues he viewed in the Paris ethnographical museum.

He created many paintings

of eminent art figures of the day such as Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Juan Gris

(1887-1927) and Jean Cocteau (1889-1963).

Although never a friend of Picasso nor a part of his inner circle,

Picasso is depicted in a portrait, Pablo Picasso

(1915, oil on canvas) by Modigliani who writes the French word connais next to Picasso probably intending

it to mean that Picasso is the one who knows, an acknowledgement of Picasso’s

genius. Modigliani often used text in

his paintings to connect his images to a certain signposted concept. His portrait of Cocteau, Jean Cocteau (1916, oil on canvas) is supremely satirical, even

cartoonish. Cocteau’s snooty, snobbish

attitudes are encapsulated in Cocteau’s implausibly elongated nose that also

implies the extent of Cocteau’s self-regard.

Cocteau apparently acquired the painting but then contrived to leave it

behind when he left Modigliani’s studio.

The exhibition includes

the usual audio guide which is dense, intense and compulsory as usual but new technology

is on display, the Modigliani VR (Virtual Reality headset), the Ochre Atelier

(yellow studio). The headset is meant to

provide an immersive experience, simulating Modigliani’s last studio complete

with damp rot, rats and cold, an artist’s reek and, finally, the stench of

death. Its not quite as immersive as

this but its good to see that the Tate Modern is bringing us up to date with

new technologies and acknowledging the important contemporary place that gaming

technology and online worlds are to artists today even if everyone inside the

exhibition looked like a trooper from the Death Star. The addition, however, seems a bit belated as

does the Tate’s overall interaction with our online, virtual world.

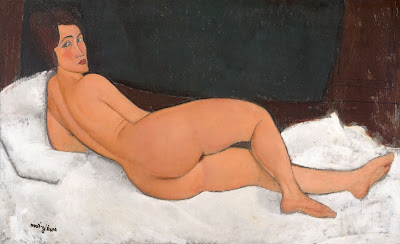

Modigliani’s signature

style had finally begun to crystallise, the human face is compressed to an

expressive oval, almond shaped eyes, a discrete nose tucked away between

reddened cheeks and an elongated, swan-like neck. Modigliani had also begun to shock Parisians

with his female nudes which clearly exist in a continuum of art history. They display a knowledge of the genre of

female nudes rather than being simply drawings of naked women. One painting which is clearly referenced is Olympia (1863, oil on canvas) by Edouard

Manet, the precursor of the modern nude depicted in works like Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907,

Matisse’s Blue Nude 1906 and Gaugin’s

Manu Tupapau 1892. In this iconic painting the figure covers her

genitals with her hand thus drawing the viewers attention to them. Modigliani, aware of the rules and

conventions of the genre, gives his nudes pubic hair and therefore sexualises

the women he paints as in Reclining Nude

(1917-18, oil on canvas), Female Nude

(1916, oil on canvas) and Reclining Nude

(1919, oil on canvas). The women are

depicted as sensuous individuals with real bodies rather than as sex

objects. Also, the models that

Modigliani used gaze out of the portraits, seemingly independent, female models

who were now well paid. Modelling was

regarded as a plausible alternative to office or domestic drudgery. The furore at Modigliani’s one and only one-person

exhibition staged during the artists lifetime in December 1917 at the Paris

gallery of Berthe Weill, a prominent dealer of avant-garde art, led to the

exhibition being closed by the police but only for a day. Modigliani’s nudes are foregrounded within

the image to the extent that their heads are often cropped away. Flesh tones are accentuated to the extent

that Modigliani’s figures are just one constant flesh tone which is being

accentuated to undermine the genre’s realist claims.

Modigliani remained in

Paris during WW1 but, towards the end of the war when the Germans began to bomb

the city, he left and departed for the Cote D’azure with his wife, Jeanne

Heburtene. Modigliani completed many

portraits of Jeanne, some of which are included in this exhibition, for

instance, Jeanne Heburtene with Yellow

Jumper (1918-19, oil on canvas) and Jeanne

Heburtene Seated (1918, oil on canvas)

Modigliani had suffered

from tuberculosis throughout his life, aggravated by his addiction to alcohol

and drugs. He hoped that a visit to the

south of France would speed his recovery.

However, he died on 24th January 1920 one year after his

return to Paris. Some five days later,

Jeanne, heavily pregnant with Modigliani’s child, took her own life.

Paul Murphy, November

2017

Comments