Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan at the Tate Modern, London, March 2012

Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan at the Tate Modern, London, March 2012

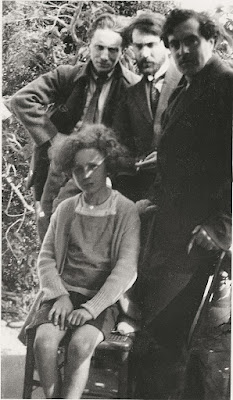

Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994)was an Italian conceptual artist connected to various movements including the Arte Povera movement of radical young Italian artists known for using simple, inexpensive materials such as biro pens, postage stamps and magazine covers. Boetti is an artist like Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) fascinated by alchemical symbols, numbers, esoteric possibly meaningless symbols, keys, codes, ciphers. His work links specific artists to certain symbols. One work links certain Turin artists to specific parts of the city set out in cartographical form with certain colours representing the domain of some artist friend of Boetti, usually another member of the Arte Povera group.

As an artist Boetti is Mettera al Mondo il Mondo (giving birth to the world) through works like sei sensi (The Six Senses, 1974), an enormous abstract made entirely with biro pens utilised at different intensities, an alphabet running down the side of the painting and apostrophes placed at arbitrary places. Another work Per un uomo alienato (For an Alienated Man, 1968) bears witness to the student movements of the '60s with its deliberate echoing of the writings of Herbert Marcuse, a key member of the Frankfurt School of neo-Marxists who took root in campuses in California after WW2.

Boetti concentrates specifically on the notion of time as something we measure in a standard, regular form yet his artworks essentially connive to somehow upset our sense of time altogether as in his work Lampada annuale (Annual Lamp, 1966) which depicts a lamp that comes on for just eleven seconds a year. Other works, such as L'albero dello ore (The Hour Tree) offer simultaneously familiar yet distanciated objects, offering us both regularity, familiarity and an alienated, eery sense of otherness. In Serie di merli dispositi intervalli regolari lungo gli spalti di una muragha (a row of merlons set at regular intervals along the ramparts of a wall.) Boetti is also asking, how much is the artist actually in control of his or her materials? Can the artist quantify the extent of this control or does each artwork leave behind the artist as it offers its own specific rules of the game?

Boetti's maps document the Cold War era. Created by embroiderers in Afghanistan, another place that Boetti seemed to occupy as well as Ethiopia and Guatemala, these maps are surrounded by Italian or Arabic texts. Since Afghanistan is a landlocked country one of the maps was returned with pink oceans and from then on Boetti allowed the embroiderers to determine the colours of the oceans themselves. The works therefore began to drift into abstraction or psychedelia but this explanation sounds like a cover story for the works were clearly completed by users of halluconogenic drugs. Boetti uses industrial materials, the titles are often frank, for instance Legnetti colorati (Little Coloured Sticks, 1968). We are left to figure out what the conceptual sculptures resemble, for instance 8,50 (Zig Zag) looks like a heap of deck chairs.

Later works insist on two familiar preoccupations of the era, classification and lists. Materials are also increasingly non-traditional, for instance Storia naturale della moltiplicazione (Natural History of Multiplication, 1975) is completed on grid paper. Boetti is trying to find significance and metaphysical drama in random patterns of symbols, dates, events, even any regularly measured things such as the pattern of integers that occur randomly in the chronology of his own life. There is always one error left deliberately in each composition. The urge towards classification and lists reaches its seeming limit in his work i mille fiumipin lunghi del mondo (The thousand longest rivers in the world, 1976-78) completed by Boetti and his partner Annemarie Sauzeau Boetti. This reflects the work of art groups like OuLiPo which were strongly influencing Boetti and Sauzeau in the 1970s. In this work the green canvas begins to take over the meaning of the work so a second version was completed on yellow ochre to make the meaning clearer.

By the mid-70s Boetti was beginning to work with more traditional materials as if to prove that he was not merely a conceptual artist. He uses collaged origami figures, water colours, Japanese red inks and frottage in works like La natura, una facenda obtusa (Nature, a dull affair, 1980), consisting of collage and ink on paper. In his last work Tutto (Everything) large scale psychedelic embroideries in garish fluorescent colours incorporating multiple images and objects plus a mix of Italian and Arabic text which are now direct calls for a new Jihad in Afghanistan, a call now seemingly fulfilled. Boetti's work is also a map of the Cold War era and though his work now seems to be typical conceptual art but ground-breaking at the time it points towards our present as some of the places that Boetti occupied, such as Afghanistan are once again filled with significance.

Paul Murphy, Tate Modern, London, March 2012

Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994)was an Italian conceptual artist connected to various movements including the Arte Povera movement of radical young Italian artists known for using simple, inexpensive materials such as biro pens, postage stamps and magazine covers. Boetti is an artist like Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) fascinated by alchemical symbols, numbers, esoteric possibly meaningless symbols, keys, codes, ciphers. His work links specific artists to certain symbols. One work links certain Turin artists to specific parts of the city set out in cartographical form with certain colours representing the domain of some artist friend of Boetti, usually another member of the Arte Povera group.

As an artist Boetti is Mettera al Mondo il Mondo (giving birth to the world) through works like sei sensi (The Six Senses, 1974), an enormous abstract made entirely with biro pens utilised at different intensities, an alphabet running down the side of the painting and apostrophes placed at arbitrary places. Another work Per un uomo alienato (For an Alienated Man, 1968) bears witness to the student movements of the '60s with its deliberate echoing of the writings of Herbert Marcuse, a key member of the Frankfurt School of neo-Marxists who took root in campuses in California after WW2.

Boetti concentrates specifically on the notion of time as something we measure in a standard, regular form yet his artworks essentially connive to somehow upset our sense of time altogether as in his work Lampada annuale (Annual Lamp, 1966) which depicts a lamp that comes on for just eleven seconds a year. Other works, such as L'albero dello ore (The Hour Tree) offer simultaneously familiar yet distanciated objects, offering us both regularity, familiarity and an alienated, eery sense of otherness. In Serie di merli dispositi intervalli regolari lungo gli spalti di una muragha (a row of merlons set at regular intervals along the ramparts of a wall.) Boetti is also asking, how much is the artist actually in control of his or her materials? Can the artist quantify the extent of this control or does each artwork leave behind the artist as it offers its own specific rules of the game?

Boetti's maps document the Cold War era. Created by embroiderers in Afghanistan, another place that Boetti seemed to occupy as well as Ethiopia and Guatemala, these maps are surrounded by Italian or Arabic texts. Since Afghanistan is a landlocked country one of the maps was returned with pink oceans and from then on Boetti allowed the embroiderers to determine the colours of the oceans themselves. The works therefore began to drift into abstraction or psychedelia but this explanation sounds like a cover story for the works were clearly completed by users of halluconogenic drugs. Boetti uses industrial materials, the titles are often frank, for instance Legnetti colorati (Little Coloured Sticks, 1968). We are left to figure out what the conceptual sculptures resemble, for instance 8,50 (Zig Zag) looks like a heap of deck chairs.

Later works insist on two familiar preoccupations of the era, classification and lists. Materials are also increasingly non-traditional, for instance Storia naturale della moltiplicazione (Natural History of Multiplication, 1975) is completed on grid paper. Boetti is trying to find significance and metaphysical drama in random patterns of symbols, dates, events, even any regularly measured things such as the pattern of integers that occur randomly in the chronology of his own life. There is always one error left deliberately in each composition. The urge towards classification and lists reaches its seeming limit in his work i mille fiumipin lunghi del mondo (The thousand longest rivers in the world, 1976-78) completed by Boetti and his partner Annemarie Sauzeau Boetti. This reflects the work of art groups like OuLiPo which were strongly influencing Boetti and Sauzeau in the 1970s. In this work the green canvas begins to take over the meaning of the work so a second version was completed on yellow ochre to make the meaning clearer.

By the mid-70s Boetti was beginning to work with more traditional materials as if to prove that he was not merely a conceptual artist. He uses collaged origami figures, water colours, Japanese red inks and frottage in works like La natura, una facenda obtusa (Nature, a dull affair, 1980), consisting of collage and ink on paper. In his last work Tutto (Everything) large scale psychedelic embroideries in garish fluorescent colours incorporating multiple images and objects plus a mix of Italian and Arabic text which are now direct calls for a new Jihad in Afghanistan, a call now seemingly fulfilled. Boetti's work is also a map of the Cold War era and though his work now seems to be typical conceptual art but ground-breaking at the time it points towards our present as some of the places that Boetti occupied, such as Afghanistan are once again filled with significance.

Paul Murphy, Tate Modern, London, March 2012

Comments