The Night Alive

The Night Alive; Written and Directed by Conor McPherson at the Lyric Theatre, Belfast

Tue - Sat 7.45pm

Sat & Sun Matinees 2.30pm

Prices

Preview (6th & 7th Oct) £13

Off-Peak (Tues - Thurs and Matinees) £15

Peak (Fri + Sat nights) £26.50

Concessions

Students, Unemployed, Under 20s & Over 65s - Any performance (except Fri & Sat evening) £10

The Lyric Theatre and Dublin Theatre Festival presents

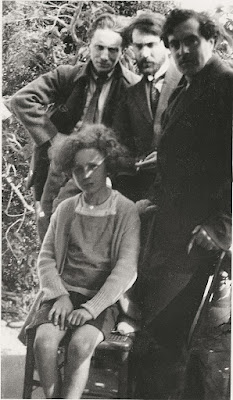

The Night Alive Written and Directed by Olivier Award Winning Conor McPherson Starring Adrian Dunbar, Kate Stanley Brennan, Laurence Kinlan, Ian Lloyd-Anderson & Frank Grimes

Set in Dublin, The Night Alive tells the story of Tommy – a middle-aged man, just about getting by. He’s renting a run-down room in his uncle Maurice’s house, keeping his ex-wife and kids at arm’s length and rolling from one get-rich-quick scheme to the other with his pal Doc. Then one night he comes to the aid of Aimee, who’s not had it easy herself, struggling through life the only way she knows how. Their past won’t let go easily. But together there’s a glimmer of hope that they could make something more of their lives. Something extraordinary. Perhaps. With inimitable warmth, style and craft, The Night Alive deftly mines the humanity to be found in the most unlikely of situations. Following acclaimed runs at the Donmar Warehouse in London and the Atlantic Theatre, New York, we're thrilled to present the Irish premiere of this latest play by the writer of The Weir, The Seafarer and Shining City, in a co-production with the Dublin Theatre Festival. The Lyric Theatre and Dublin Theatre Festival are proud to present a new production of Conor McPherson’s The Night Alive, directed by the author and with an all-star cast, which will open the 2015 Belfast Festival. Running Time: 1 Hour 45 minutes with no interval. On Friday I attended the inaugural event of the Belfast International Festival which turned out to be a play, The Night Alive by Conor McPherson author of The Weir. The title lacked something perhaps because it seems vague and pointless. The play focusses on the trials of the central character Tommy who lives in a formless squat but actually his uncle Maurice’s Dublin house with a further character, Doc, a young homeless man with learning disabilities. The matter of economy is dealt with via an elementary deus ex machina, a stash of cash hidden under the floorboards. The play was reminiscent of a Sean O’Casey play such as Shadow of a Gunman where the action and characterisation is condensed into one constantly oppressive location. In other words, a horrid room in a tenement, a formless, hopeless place where the dispossessed fail and fail to fulfil their destinies. Unlike O’Casey the play is emptied of the urgent political message of the 1920’s and instead events are given a social perspective which is hardly ever didactic or even direct. Its certain that we are not dealing with the lives of the working classes since the characters are a rung below this, indeed they are virtual members of the underclass. People who long to be robustly proletarian, to belong. Everything changes for Tommy when he discovers a young woman Aimee who has been brutally beaten by her boyfriend Kenneth. She decides to stay and offers Tommy sexual favours in exchange for rent. The sordid and mean tale of a hooker, her pimp and some rather dull, eventless happenings which might be better left unsaid unfolds. Unlike Shakespeare or Sophocles whose tragedies unite pity and terror and thereby evoke sympathy there is little here to be cheerful, positive, optimistic or hopeful for. Paradoxically the form of the play is robustly in favour of the unities outlined by Aristotle and therefore conservative and condensed as a result without the need even for an interval. However, it hardly could be said that the text lay dead on the page for the texture of the language and its colloquial basis was always energising if nothing else especially Doc’s musings about the origins of the universe, time and black holes which seems somehow topical given the recent film biography of Stephen Hawking. Doc is a rather trite fool, victim and idiot savant and very like one of O’Casey’s fools. Tommy is ably played by Adrian Dunbar indeed his performance is the keynote of the entire production binding all the other strands together. In the final act Kenneth has been killed in a terrible brawl after beating Doc with a hammer. Tommy is planning to flee Dublin for Finland (well they could always go to a Sibelius festival or play among the reindeer...) but Aimee, probably sensibly, refuses to go. Moral distinctions are hardly blurred in the play, indeed the characters might as well wear black and white hats. For that is how the author intends us to see his characters as representatives of virtue or vice, as types or stereotypes. The fallen woman, the hero who rescues her, the viscous cad, the fool. It seems that we are being fed a dose of sentiment in the form of a would-be Victorian melodrama written by and for the landlord Maurice who lives upstairs, reclining above the cast in God-like omnipotence. He offers all kinds of trite, sage advice to Tommy and descends ultimately, an avatar, to provide a commentary about the proceedings or just to draw a thin veil over events. The biggest problem with the play is the ending which seems to explode with all the force of a damp squib. This is a case of the night dead and nothing else but it has to be said that the audience seemed pleased.

Paul Murphy, the Lyric Theatre, Belfast

The Lyric Theatre and Dublin Theatre Festival presents

The Night Alive Written and Directed by Olivier Award Winning Conor McPherson Starring Adrian Dunbar, Kate Stanley Brennan, Laurence Kinlan, Ian Lloyd-Anderson & Frank Grimes

Set in Dublin, The Night Alive tells the story of Tommy – a middle-aged man, just about getting by. He’s renting a run-down room in his uncle Maurice’s house, keeping his ex-wife and kids at arm’s length and rolling from one get-rich-quick scheme to the other with his pal Doc. Then one night he comes to the aid of Aimee, who’s not had it easy herself, struggling through life the only way she knows how. Their past won’t let go easily. But together there’s a glimmer of hope that they could make something more of their lives. Something extraordinary. Perhaps. With inimitable warmth, style and craft, The Night Alive deftly mines the humanity to be found in the most unlikely of situations. Following acclaimed runs at the Donmar Warehouse in London and the Atlantic Theatre, New York, we're thrilled to present the Irish premiere of this latest play by the writer of The Weir, The Seafarer and Shining City, in a co-production with the Dublin Theatre Festival. The Lyric Theatre and Dublin Theatre Festival are proud to present a new production of Conor McPherson’s The Night Alive, directed by the author and with an all-star cast, which will open the 2015 Belfast Festival. Running Time: 1 Hour 45 minutes with no interval. On Friday I attended the inaugural event of the Belfast International Festival which turned out to be a play, The Night Alive by Conor McPherson author of The Weir. The title lacked something perhaps because it seems vague and pointless. The play focusses on the trials of the central character Tommy who lives in a formless squat but actually his uncle Maurice’s Dublin house with a further character, Doc, a young homeless man with learning disabilities. The matter of economy is dealt with via an elementary deus ex machina, a stash of cash hidden under the floorboards. The play was reminiscent of a Sean O’Casey play such as Shadow of a Gunman where the action and characterisation is condensed into one constantly oppressive location. In other words, a horrid room in a tenement, a formless, hopeless place where the dispossessed fail and fail to fulfil their destinies. Unlike O’Casey the play is emptied of the urgent political message of the 1920’s and instead events are given a social perspective which is hardly ever didactic or even direct. Its certain that we are not dealing with the lives of the working classes since the characters are a rung below this, indeed they are virtual members of the underclass. People who long to be robustly proletarian, to belong. Everything changes for Tommy when he discovers a young woman Aimee who has been brutally beaten by her boyfriend Kenneth. She decides to stay and offers Tommy sexual favours in exchange for rent. The sordid and mean tale of a hooker, her pimp and some rather dull, eventless happenings which might be better left unsaid unfolds. Unlike Shakespeare or Sophocles whose tragedies unite pity and terror and thereby evoke sympathy there is little here to be cheerful, positive, optimistic or hopeful for. Paradoxically the form of the play is robustly in favour of the unities outlined by Aristotle and therefore conservative and condensed as a result without the need even for an interval. However, it hardly could be said that the text lay dead on the page for the texture of the language and its colloquial basis was always energising if nothing else especially Doc’s musings about the origins of the universe, time and black holes which seems somehow topical given the recent film biography of Stephen Hawking. Doc is a rather trite fool, victim and idiot savant and very like one of O’Casey’s fools. Tommy is ably played by Adrian Dunbar indeed his performance is the keynote of the entire production binding all the other strands together. In the final act Kenneth has been killed in a terrible brawl after beating Doc with a hammer. Tommy is planning to flee Dublin for Finland (well they could always go to a Sibelius festival or play among the reindeer...) but Aimee, probably sensibly, refuses to go. Moral distinctions are hardly blurred in the play, indeed the characters might as well wear black and white hats. For that is how the author intends us to see his characters as representatives of virtue or vice, as types or stereotypes. The fallen woman, the hero who rescues her, the viscous cad, the fool. It seems that we are being fed a dose of sentiment in the form of a would-be Victorian melodrama written by and for the landlord Maurice who lives upstairs, reclining above the cast in God-like omnipotence. He offers all kinds of trite, sage advice to Tommy and descends ultimately, an avatar, to provide a commentary about the proceedings or just to draw a thin veil over events. The biggest problem with the play is the ending which seems to explode with all the force of a damp squib. This is a case of the night dead and nothing else but it has to be said that the audience seemed pleased.

Paul Murphy, the Lyric Theatre, Belfast

Comments