Van Gogh and Britain at the Tate Britain

VAN

GOGH AND BRITAIN

At

the Tate Britain, July 28th, 2019

Today at Mill Bank. A

washout meant that I could cover Van Gogh and Britain, a far-fetched

poetic fantasy about the artist’s early youth. Tons of collaborators admitted

to knowing him after he was made into an icon. It is difficult to learn from

Van Gogh's inimitable style and fatal to imitate it but terms like ‘asylum’, ‘fallen

woman’ and ‘lunatic’ mean that the narrative fashioned about his life is

undeniably entertaining.

Van Gogh and Britain

follows a brief chronology before unfolding into a discourse on the artist’s

imitators and those he influenced. The

implied message is that Van Gogh (1853-1890) is actually very close to us. For instance, he lived for three years in

London, between 1873 and 1875, initially working for an art dealer called

Goupil before subsiding into depression, unrequited love and eventual

unemployment as he was dismissed from his post.

Afterwards he left for the Borinage in Belgium to begin a career as a

lay preacher. This was to be yet another

disastrous move and false start for Vincent as his artistic nature conflicted

with the philistine hypocrisy of the church.

He lived in places

familiar to us today as inner London, Stockwell and the Oval, but in Van Gogh’s

day these were villages only recently absorbed into the nascent spread of the

capital. Van Gogh was not yet an artist,

but he had begun to be influenced by British art, works like John Everett

Millais’s, Chill October (1870, oil on canvas). Chill October has no subject to

enliven the landscape and people therefore speculated that it must be about the

transience of life. Moreover, it showed

Millais gravitating away from the Pre-Raphaelite style of his earlier years

towards brooding, melancholic landscapes rendered by the techniques of

photographic realism. Van Gogh enthuses

about the work in yet another letter to Theo.

We learn that he had an affinity with Scotland through the artist

Archibald Hartrick (1864-1950) who wrote a book about the artist perhaps to

cash in on Van Gogh’s posthumous reputation.

However, his portrait of Van Gogh on the fly leaf of his eponymous book

is original and compelling just as Van Gogh’s own self-portraits are. Hartrick also worked at Pont-Aven in Brittany

with Paul Gaugin in 1886 before Gaugin’s departure to Arles. He knew Toulouse-Lautrec (an artist who

scrupulously avoided Van Gogh) and exhibited a work in the Paris salon

in 1887. Another Scot, Alexander Reid

(1854-1928), an art dealer, roomed with Van Gogh in Paris.

Van Gogh was enthusiastic

about British culture too, spoke and read English. He particularly enjoyed the works of

Shakespeare, Christina Rossetti and Charles Dickens. His interest went beyond literature, he

collected 2,000 engravings from British magazines and newspapers. His sole aim was to visualise the works of

Dickens: “My whole life is aimed at making the things that Dickens describes

and these artists draw.” Although the

exhibition is stuffed full of things that disappear off in multitudinous

directions, the sheer enthusiasm for its subject is infectious and

inspiring. The exhibition traces Van

Gogh’s influence on British culture through an exploration of early London

exhibitions of his paintings from which the implied legend of Van Gogh’s

insanity and genius began to arise.

After WW2 the Tate’s exhibition of Van Gogh’s works began to inspire the

public again, the Arts Council, founded in 1946 put on an exhibition of Van

Gogh’s paintings and 5,000 visited every day.

This became known as ‘the Miracle on Mill Bank’ and the exhibition was

again popular when it went on tour to Birmingham and Glasgow. Perhaps the struggle and belated popularity

of the artists appealed to a generation who had been mired in war, but the

artist found a new audience when his life became the subject of Hollywood

biopics. These new cinematic renderings

such as Vincente Minelli’s 1956 film Lust for Life which depicted the

relationship between Van Gogh and Gaugin, depicted Van Gogh as a new kind of

man, almost a unique addition to evolution.

The banal conclusion, that Van Gogh and Gaugin were more than friends,

was still heart-rending for people of that time. John Wayne was moved to declare to Kirk

Douglas, after viewing the film’s wrap “…Kirk, how can you play a part like

that? There’s so…few of us left. We got to play strong, tough characters. Not those weak queers.”

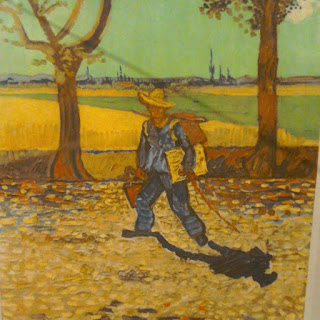

An example of Van Gogh's influence

on British art is a book reproduction of his work The Painter on the road to

Tarascon (1888) in which Van Gogh depicts himself as a lone, eccentric yet

intrinsically heroic figure subsumed by his own shadow cast on the road. (The original was destroyed by Allied bombing

in the war. Another work by Van Gogh was destroyed in the bombing of Hiroshima underscoring

the interest that the Axis showed in Van Gogh's art.) In Francis Bacon's interpretation of the

original, Study for ‘Portrait of Van Gogh IV’ (1957) the subject is not

art but the shadow the artist casts. Van Gogh's reputation is far more powerful

than his work and the evidence of this was the crowds at Mill Bank. Bacon said of Van Gogh: ‘Van Gogh is one of

my great heroes…[He] speaks of the need to make changes in reality…This is the

only possible way the painter can bring back the intensity of the reality.’ Featured side by side with Bacon’s

depictions of Van Gogh is one of the last self-portraits completed by the

artist, Self-Portrait, Saint-Remy, autumn 1889 (oil paint on

canvas). Although the artist seems emaciated

(Van Gogh was in the Saint-Paul hospital after a further bout of depression in

the summer of 1889 and wrote about the experience that he ‘began the first day

I got up, I was thin, pale as a devil.’).

The artist grasps a palette as if his life depended on it, a possible

message to his brother that he was once again quite bright and active.

As unfocussed and

rambling as it is Van Gogh and Britain may prove to be another ‘Miracle on Mill

Bank’.

Paul Murphy, Tate

Britain, July 2019

Comments