Alfred Wallis at The Mac, Belfast on the 29th of January 2022

Alfred Wallis at The Mac, Belfast on the 29th of January 2022

On Saturday I went to see

an exhibition of the work of Alfred Wallis at The Mac, Belfast. Wallis was a mariner, a native of St Ives,

born on the eve of the Battle of Sevastopol at the height of the Crimean war in

1855. He was a sailor and fisherman on

trawlers and deep-sea fishing boats, and these, as well as port landscapes,

were the main subjects of his art. Wallis was diminutive, possibly only 4 foot 6 and his origins were in Penzance. He was never, apparently, accepted by the natives of St Ives.

Like many primitive

artists, Wallis began painting later in life, at the age of 67 after the death

of his wife. She happened to be 23 years older than Wallis and their relationship was seen by one of Wallis's earliest biographers as 'Oedipal'. When he retired from his

life as a sailor, he became a rag and bone man and created many of his artworks

using the cardboard, boxes, and bits of wood that he found. The materials often dictate the shape and

dimensions of the paintings. Wallis

often leaves part of his improvised canvases empty, probably to indicate the

primitive origin of the materials he employed. An example of this is in his work The Blue Ship where he leaves the spaces between the masts and rigging blank. The orange card, therefore, is seen, rather than the seascape. However, the contrast seems to work since two complimentary colours are brought together.

Wallis had no formal art

training, and he seems to have been unconcerned with formal recognition. Other natives of St Ives had also taken up painting or model making later in life. In fact, St Ives was changing from dependence on the fishing industry to tourism. Painting, or culture generally, was becoming more central. Although his works often ignore perspective

and even scale, they have a freshness, vividness and excellent impasto

brushwork that demand our attention. His

subject is the rigged sailing ships of his youth. These ships collide with giant fish which are

at least the same size as the ships, Moby Dicks that are also the cod and

haddock that were the vital catch for the ships he worked. On land, giant horses and foxes run past the egg

box houses that pepper the foreshore.

But Wallis's subject is always the sea and its precarity, beauty and

oddness.

He lived with the constant fear of the workhouse which he had to go to in 1941, at the very end of his life. He spent a year at the Madron workhouse near Penzance before departing this life in 1942. His work was discovered by members of the London set like Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood who came to St Ives in the 1920s to establish an artist's colony. 'Discovered' is a debateable term since it implies that Wallis did not realise that what he was doing was art. Nicholson said that Wallis's art is 'something that has grown out of the Cornish seas and earth and which will endure.' Wallis also feared being buried in a pauper’s grave but his art friends ensured that he had a proper burial with a headstone by Bernard Leach and an epitaph written by W.S.Graham, taken from Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The headstone depicts a figure climbing the steps to a light house, implying that Wallis is the lighthouse keeper, providing illumination and guidance to future artists.

In Wallis’s painting P

& O ship (n.d. oil on canvas) the horizon line is pushed to the limit

of the canvas, a recurring feature in many of his works. Wallis clearly understood some of the basic

rules of perspective. His vigorous

impasto painting conveys the swirling waves that threaten to overcome the P

& O ship. The steamship is rendered

with exactitude. The contrast between

the child-like lapses of perspective and scale and the exactness of his

diagrammatic drawings is a recurring feature of Wallis’s painting and seem to

ask a question, how primitive are Wallis’s paintings really?

His work Motor vessel

with Airship and Shark (n.d. oil on canvas) features an airship hovering in

the sky. A shark lurks in the blue

depths of the sea. The vessel is rendered

in black with unfeasibly large black figures on deck. The painting seems to point to the future of

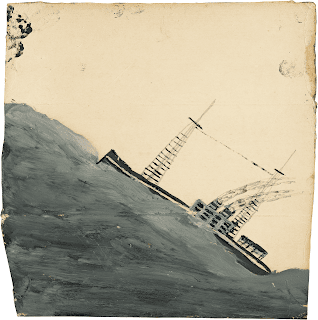

air travel and to the ancient depths and primordial terror. In Motor vessel mounting a wave (n.d.

oil and graphite on card) a steamship struggles to surmount a wave. Grey swirling impasto paintwork implies the

steel grey sea of the north Atlantic.

The sky is blank, unpainted card. In Brigantine sailing past green

fields (n.d. oil on card) both ship and background are of equal

importance. The horizon line is once

again pushed to the top of the canvas.

The sea is depicted with powerful impasto brush strokes. The fields in the background overshadow the

tall, three-masted ship. The simplicity

of Wallis’s palette provides further powerful contrasts. A vivid sunset is implied via the orange card

that Wallis used in Sailing Ship against a sandy beach (n.d. oil on

card). The land juts out at the top of

the painting, vying to absorb either ship or sea.

Most of Wallis’s

paintings are undated. His work Death

Ship (1941-2, oil on dark brown card) was painted in the last year of the

artist’s life. The ship is painted in

black with white highlights that seem to guide the eye around the ship’s form. The waves are rendered with thick, white

impasto. The ship is at least a portent

but also a vehicle to carry the body of the artist across the divide, from life

to death. Wallis’s paintings are at last

filled with foreboding.

Wallis’s painting began to attract the

attention of artists and critics at a time when the certainties of established

art such as perspective were being increasingly challenged by movements like

primitivism, expressionism, and modernism.

Wallis’s work is comparable to that of the expressionists who also

shared a common basis in rejecting qualities like perspective or scale although

probably through a more educated awareness of what the rules were, what they

meant, and why they could and should be broken.

His works also reflects on non-western cultures that created

art unaware of the established discourse of art. It also considers the division between the

irrational and rational. Why did Wallis persist? The answer must be that he was ‘mad’. After all his art was useless, the work of a

man going through a second childhood. At

one point Wallis considered giving his paintings to Dr Barnardoes which demonstrates

an underlying awareness of critical issues surrounding his work but also his religious committment to charitable works. Wallis implicitly realised the connection

between primitive art, primitive cultures, and the irrational, and realised that

his paintings were valuable and valid.

But it is Wallis’s appreciation of the

power of the sea and ships and their crews who sailed on it, that is the most

palpable demonstration of his legacy.

Comments