Kyosai at the Royal Academy on the 21st, April 2022

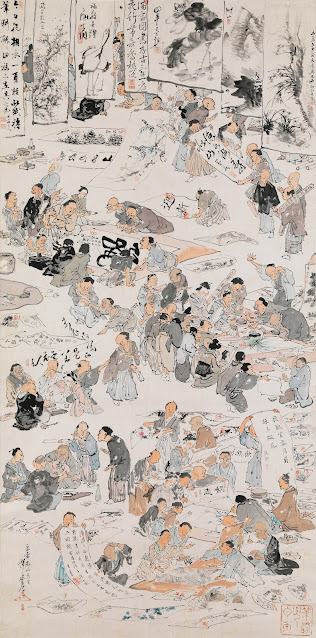

Kawanabe

Kyosai (1831-1889 is regarded as the successor in Japanese art to Katsushika

Hokusai (1760-1849) who helped to shape the Ukiyo-e (floating world)

painting style. Whereas Japan had been

relatively isolated from the outside world for 260 years,

Kyosai witnessed the arrival of the first western fleet and increasing

Westernisation.

This

was initiated by the Meiji dynasty in 1868 when the Tokugawa shogunate was

toppled and imperial power restored after centuries of decline. The emperor had come to represent spiritual

power whereas, the Shogun (meaning roughly ‘army commander’) the secular, military

power of the Japanese state. Although

the Shogun was technically the emperor’s servant, the emperor had been

marginalised and deprived of significance for centuries. The Meiji restoration signified the decline

of the shogunate. The emperor moved his

seat of power from Kyoto to Edo, formerly the capital of the shogunate,

re-naming it Tokyo.

Meiji,

meaning Enlightened Rule, represented a historic alteration in Japanese foreign

and domestic policies. Regional

landlords or daimyos voluntarily surrendered their land to the emperor and

increasing reliance on Western experts and Western products like meat and beef

became a new normal.

Kyosai,

therefore, lived in turbulent times. He

initially studied under Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861) an adept of the ukiyo-e

(floating world) style. Ukiyo-e had

different connotations, meaning “erotic” or “stylish” and signified “living for

the moment…like a gourd carried along by the river current.” (Asai Ryoi, Ukiyo

Monogatari – Tale of the Floating World, 1661). After studying under Kuniyoshi, Kyosai then

studied in the Kano school, the dominant school of art in Japan organised by

the shogunate and the samurai. It was

here that Kyosai learnt to incorporate Kano-style ink techniques into his

drawings.

In

Night Procession of 100 Demons (1871/89, ink and gouache on paper) an

ancient Japanese tradition that stated that household items more than

100 years old are transformed into demons that come out at night and are

vanquished at sunrise. Pots, potlids,

and plates protrude from the demons. Thick,

austere black lines are complimented by pastel shades of blue, pink, and grey.

Many

of Kyosai’s works represent the natural world, such as Egrets over lotus

pond in the rain (1871/89, ink on paper).

Works like this evoke the traditional stillness and minimal concentration

of a Japanese haiku. In other paintings like

Fashionable picture of the Great Frog Battle (1864, colour woodblock

print triptych), the battle at the Hamaguri Gate of the Imperial Palace in

Kyoto which led to the overthrow of the Tokagawa shogunate, the use of animals

allowed Kyosai to evade censorship.

Comic

and satirical effects began to appear in Kyosai’s art, especially in relation

to the increasing Westernisation which was occurring in later 19th

century Japan. In Skeleton Shamisen

player in top hat with dancing monster (1871/78, ink and light colour on

paper), Westernisation is the target.

People may wear different disguises, such as top hats, Kyosai intimates,

but a samurai sword still sticks out from behind the skeleton. The artist seems to say that tradition will

overcome modernisation. Other

encroachments, such as the arrival of Christianity, are satirised in Kyosai’s

work Five Holy Men (1871/87, ink and light colour on paper) where Christ

is depicted on the cross waving a Japanese fan.

Attempts

to satirise Western fashions and customs did not stop Kyosai from incorporating

Western techniques such as perspective, shading, and the study of anatomy, into

his paintings. In works like A Beauty

in front of King Enma’s mirror (1871/89, ink colour and gold on silk)

Kyosai broke with convention by using a complex technique to depict comic

content.

Erotic

and satirical, religious, and secular, Kyosai’s paintings depict a world in

flux where static symbols and tradition itself, were beginning to be

questioned. This exhibition is an

excellent accompaniment to the British Museum’s recent Hokusai exhibition. In the late nineteenth century Japanese art

was beginning to capture the attention of Western artists like Van Gogh and

Paul Gaugin who began to incorporate Japanese elements into their own painting. This exhibition shows us how influence was

also flowing in the opposite direction.

Paul

Murphy, Royal Academy, April 2022

Comments