Alexander Calder at the Tate Modern

Alexander Calder 1898 – 1976 at the Tate Modern

Alexander Calder was born in New York City in 1898 and by 1919 had earned a degree in mechanical engineering. He studied art and worked as an illustrator, notably for Barnum and Bailey’s Circus.

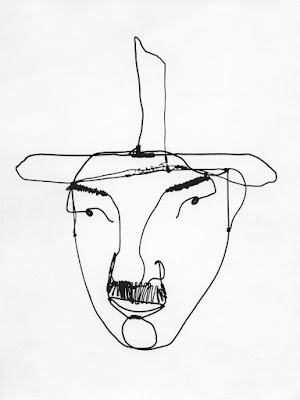

Calder’s work encompassed new use of materials, experimental projects utilising manual and then mechanical means of propulsion such as his early work Goldfish Bowl (1908) and sculptures composed solely of wire bent and shaped with pliers. These are really line drawings in three dimensions, the originality of these innovations can be seen in his early work Hercules with Lion (1908). Calder’s critics defined this work as “drawing in space”.

Then in 1926 he departed for Paris which was at that time the HQ of the international avante garde, a swinging, liberated place where the conservative values and ubiquitous racism found in America was hardly tolerated. In another early work from his Paris years Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere (1932/3) Calder creates a multi-dimensional, multi-functional art machine where two spheres push against a variety of objects. The uniqueness of this work is that it can be regarded as a sculpture or a musical instrument or both. Calder had begun to invent a new vocabulary of art for a new era. He is also credited as the inventor of the mobile but this seems to be the least of his innovations.

During his Paris years he interacted with various members of the avante garde being particularly influenced by the work of the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian whose studio he visited. Like Mondrian Calder realised that his abstract constructs were actually models of a new society in which subjects would interact freely. Thus the constructs suggest not only the spatial relationships of subjects but also the societal. He also made intricate wire sculptures of notable Parisian personalities and other members of the avante garde such as the painters Joan Miro and Fernand Leger, the composer Edgard Varese and the cabaret sensation, famous for her banana dance and a notable African American émigré, Josephine Baker. Calder’s enthusiastically unpretentious and vitally curious work caused quite a stir in Paris, especially his Cirque Calder which was seen by artists such as Miro and Jean Cocteau.

Later still Calder lent his support to the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War by providing practical solutions to their mining requirements. In 1937 he was one of the contributors to Josep Lluis Sert – designed Pavilion of the Spanish Republic at the International Exposition in Paris, the only non-Spaniard to be included. He also created a fountain that would run with the mercury from the mines of Almaden.

By 1933 Calder had moved to an old farm near Roxbury, Connecticut. Calder was formulating the total concept of the mobile which was the artwork that defined the 1950s. It was to be perfectly harmonised with the sum of its parts moving together disparately then harmoniously. It was also meant to produce sounds when blown upon. The mobiles could then exist in the sound dimension. A precursor to the mobiles were engine driven installations that produced vivid visual symmetries, a ‘quasi-astral dance’. In Calder words: “With a mechanical drive, you can control the thing like the choreography in a ballet,” (1937). Calder was able to take the new forms implied by the Cubist and Futurist projects to their logical conclusions, to create artworks that exist in different planes simultaneously, fulfilling different functions within a balletic yet controlled movement. Calder is close to giving a will to his own artworks, to offer them an independent, autonomous existence where they fulfill their destinies to move in swirling symmetry.

Calder was still perplexed by his own art and its connection to conventional canvas and easel works so that he began to create new works in the 1930s that were based on a canvas and coloured shapes suspended in front as in his Blue Panel (1936). By rotating the shapes abstract designs were projected onto the canvases, abstractions that alter, change, turn and sway. A two-dimensional image was taking on the attributes of a three-dimensional one but Calder’s mobiles, designed over the next decade define a three-dimensional creation that exists in space and has no solid space to occupy.

For the New York World Fair of 1939 Calder created models for three ‘ballet-objects’ such as the maquette Untitled 1938. This model enacts a choreographed dance of elements all set upon a miniature stage. In 1951 Calder said: “The underlying sense of form in my work has been the system of the Universe.” Calder began to see the connection between his mobiles and cosmological models of the universe which produced his works A Universe which was admired by Albert Einstein and Constellations (1943). Calder said: “I was interested in the extremely delicate, open composition.” He went on to say: “It was a very weird sensation I experienced, looking at a show of mine where nothing moved.”

At this time Calder’s work had begun to be less geometric and more organic in form, leading to his works Vertical Foliage and Snow Flurry I which drew obvious parallels with the natural world. Calder said of his mobiles that they would work with “each element able to move, to stir, to oscillate, to come and go in its relationships with other elements in its universe.” Calder’s mobile arrangements of the 1940s began to incorporate elements of sound, small hanging beaters would be put into motion at irregular intervals, producing musical notes. His work came to the attention of the musical avante garde who were committed to some sense of ‘open composition’. Experimental artworks began to be thus opened up to elements of contingency or chance, accidents or happenings in the days of conductor and performers were soon being incorporated into new musical offerings.

Calder also visited Brazil in 1948, bringing his work to Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo and thus influenced Brazilian artists such as Helio Oiticica, Lygia Clark and the Neo-Concrete movement. The final work of the Calder exhibition is his Black Widow (1948) which was donated by the artist to the Institute of Architects of Brazil in Sao Paulo. This unique sculpture is the epitomy of Calder’s technique, illustrating his ability to create large scale works of multi-dimensionality, unpretentious in their concept and coherence.

This is a very friendly exhibition offering us the chance to get to know Alexander Calder, an artist with a bumptious personality who invites us to share in his life and its peaks and troughs which are rather like our own.

Comments